Leonora Carrington: An Appreciation

The Rise of Surrealism's Forgotten Feminist Witch

Leonora Carrington: An Appreciation

The Rise of Surrealism's Forgotten Feminist Witch

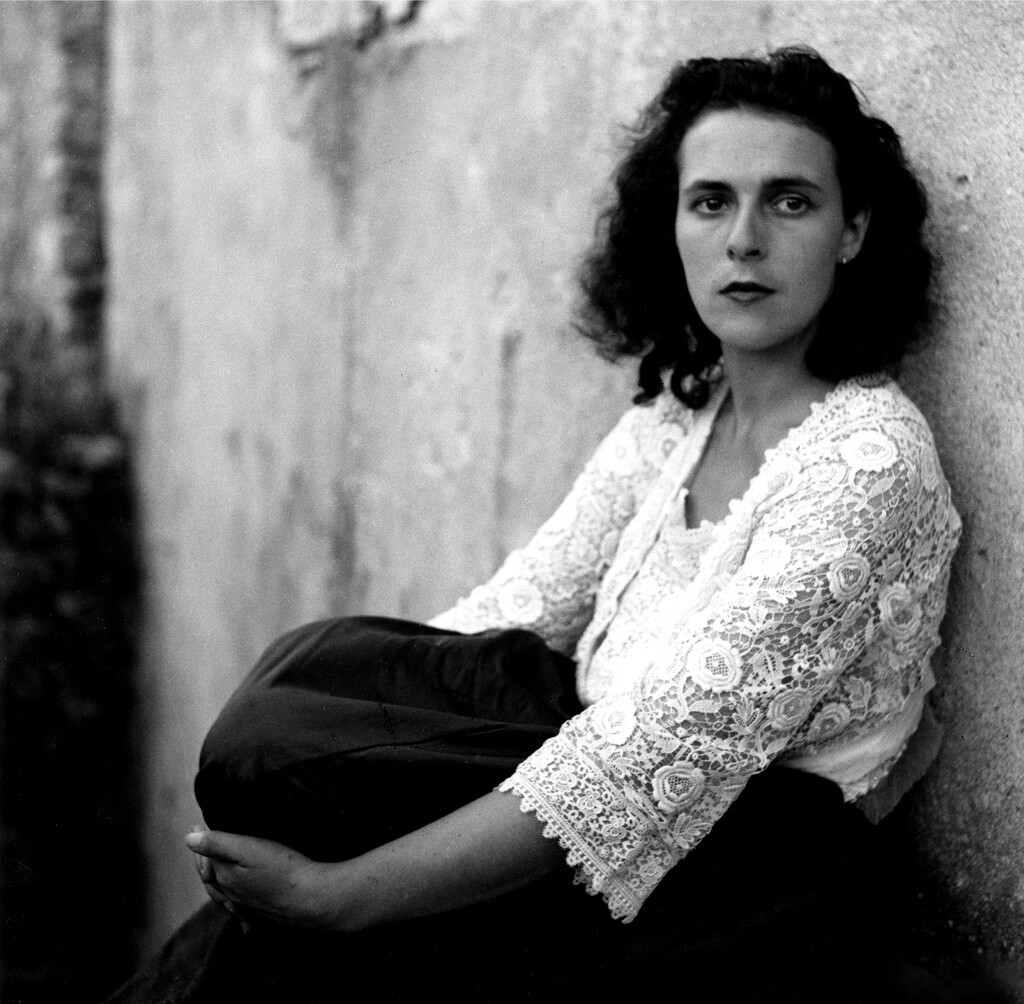

More than a decade after her death in 2011, Leonora Carrington’s star is on the rise. The Surrealist artist and writer is everywhere: Her artworks are setting record sales, and last year she became the most valuable British-born female artist at auction. A new biopic, Leonora in the Morning Light, is premiering in select countries this month, and her long-out-of-print novel The Stone Door will be reissued by New York Review of Books on July 22, introducing a new generation to her strange, sparkling prose.

Why now, after decades in which Carrington was often considered Britain’s “forgotten” surrealist? Is it her blend of fantasy and humor, her fierce feminism, her lifelong refusal to conform?

The answer, of course, is all of the above. Maybe the world is finally catching up to what Carrington knew: imagination is a weapon, survival an art, and women’s stories are worth telling—especially the wild ones.

Born in 1917 in Lancashire, Carrington was always something of a rebel. By age 17, she’d already proven herself unwelcome at two convent boarding schools, and her parents had decided that her best chance for a future lay in finding a “suitable” (i.e. rich) husband. The result was a season in London, made possible by her father’s career as an extremely successful textile manufacturer, and a presentation at Buckingham Palace in a satin designer gown, which thrilled her mother half to death.

Yet Carrington called the whole deb thing a “cattle market.” Bored out of her mind at the Ascot races after the royal tea party, she brought a book and read it all the way through. Many years later, she recalled that the book in question was Huxley’s Eyeless in Gaza; she also remembered the sensation of the tiara biting into her skull.

The season ended up a wash as far as her parents were concerned, but two important things happened that spring of 1935—important for her and important for us. The first is that her coming-out season gave Carrington the material for her most famous short story, “The Debutante,” written in 1939. Describing the plot of a Surrealist short story can be a bit awkward, like re-telling a dream, but suffice to say that in her tale, a thinly disguised Carrington is liberated from attending a ball by a quick murder and a friendly, if hungry, hyena with whom she changes places. The wit is bone-dry and pitch-black, the satire of social mores as biting as that tiara. It is also deeply telling that in the story Carrington has rejected “suitable” company for the presence of a wild animal and, ultimately, being left alone to read her book.

Her season as a deb also got Leonora from Northern England to London, where she fell in love. Not, initially, with a man, but with his paintings. The first time she encountered Max Ernst’s work (specifically Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, she thought, “Ah, this is familiar: I know what this [is] about. A kind of world which would move between worlds. The world of our dreaming and imagination.”

Then she fell in love with Ernst himself. Carrington had convinced her parents to let her enroll in a London art school; it was at a dinner party thrown by a fellow student at the Ozenfant Academy of Fine Arts that she at last crossed paths with him. They instantly clicked, and the two entered into a world of dreaming and imagination together for a time, despite the fact that the German-born Ernst was more than two decades older, married, and a father. Needless to say, Carrington’s parents were aghast, but it didn’t really matter—by then she had proven herself someone determined to go her own way. She later recounted that her first day with Ernst, spent in the country experimenting with art techniques, was like “a whole world opening.”

Ernst was living in Paris at the time, at the center of a circle of Surrealist artists and writers that included Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dali, André Breton, and other names that would become among the most important in 20th century art. Carrington joined Ernst in Paris in the fall of 1937. While she adored the freedom of her new life, she wasn’t unduly impressed by many of the Surrealists. Mostly they were much older men who, she later informed her cousin and biographer Joanna Moorhead, “weren’t that interested” in her. Some of them even treated her as subservient, in keeping with attitudes toward women at the time. But Carrington pushed back: When Joan Miró told her to go get cigarettes for him, she said he could “bloody well get them himself.” She dismissed the Surrealist association of woman-as-muse with one word: “Bullshit.” She didn’t read Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto either, explaining later, “I didn’t want anyone else to tell me what to do or what to think.”

Breton, at least, appreciated Carrington. He described her as “superb in her refusals, with a boundless, human authenticity.” This idea of being deeply human (while exploring non-human spheres) is at the core of Carrington’s work. She was also specific about the kind of human she was, memorably describing herself as a “female human animal.” Indeed, her work radiates a feminist consciousness: women are at the center of the action, often shown in states of transformation, deep play, or occult work. In her 1942 painting Green Tea, a female figure is wrapped in cow-print shroud (or is it a straightjacket?), her eyes closed, while a headpiece topped with spikes seems to protect her dreaming. Meanwhile, a purple, egg-shaped vessel rests nearby, and a vicious-looking dog with huge udders protects the entrance to a garden whose shape suggests a womb. Though Carrington was against any kind of intellectual interpretation of her work—she preferred an emotional engagement—she turned to themes of the sacred feminine, and feminine independence, again and again.

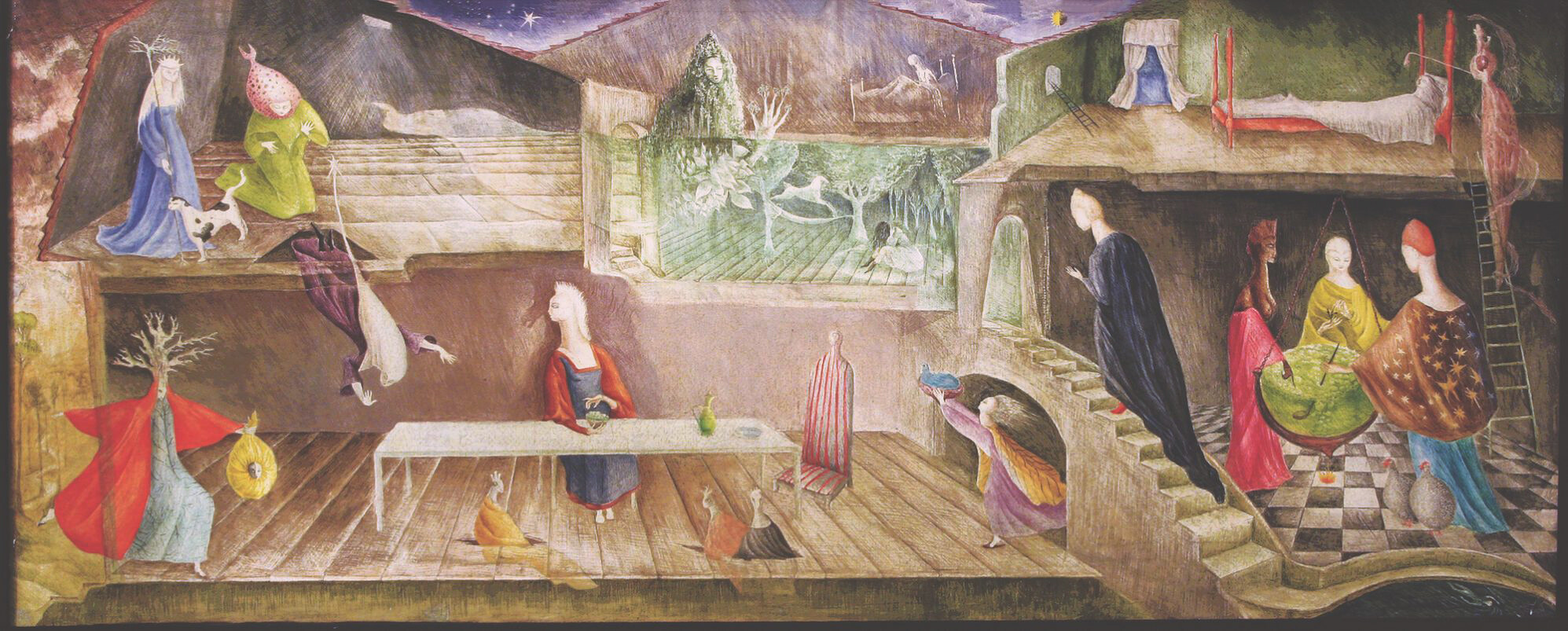

She was also fascinated by ideas of interconnectedness, particularly between the human, non-human animals, nature, and the unseen world. In her 1945 piece The House Opposite, a bevy of women (although some of them might also be horses, or trees) scurry up stairs, rush through doors, or fall through floors. Such fascination speaks to an ecological consciousness Carrington displayed throughout her life, long before such things were fashionable.

Food and cooking is another theme in her artwork. For Carrington, art, cooking, and spells or rituals were all interrelated. She described making art as a need, very much like food, and told Moorhead she considered the kitchen and studio “parallel spaces.”

The kitchen was where Carrington spent a lot of time once she settled in Mexico City. She arrived there in 1942, after fleeing the outbreak of fascism in Europe. She was far from the only artist and writer to land in Mexico—the Spanish painter Remedios Varo, French poet Benjamin Peret, Swiss photographer Eva Sulzer, and Hungarian photographer Kati Horna, among others, also arrived. One person who didn’t was Max Ernst—in France, he’d been arrested twice as an enemy alien, prompting Carrington to suffer a nervous breakdown. A friend convinced her to flee the invading Germans and go to Spain, where she was institutionalized for six months, an experience that later fueled both a painting and a book called Down Below.

Ernst eventually escaped (and began a relationship with the American collector Peggy Guggenheim), but he and Carrington never really resumed their relationship. Instead, Carrington married Mexican diplomat and poet, Renato Leduc. The relationship wasn’t exactly true love, but it got her to Mexico, a country where she felt relatively safe from the Nazis.

In the kitchen of her old house at 194 Calle Chihuahua, Carrington often spent time with Remedios Varo and Kati Horna, working on their art and domestic duties together. She soon split up with Leduc, and fell in love with Emerico “Chiki” Weisz, a Hungarian photographer and Holocaust survivor who became her husband and the father of their children. If the kitchen has historically been a place of servitude for women, this one in Mexico City was a place where Carrington, Varo, and Horna “could be exactly what they wanted to be, a place where they were truly free,” Moorhead writes in her biography of Carrington, Surreal Spaces. Their children played together, food bubbled on the stove, and the house was filled with art and love.

Carrington’s deeply human spirit comes through strongly in her writings, too. Besides “The Debutante,” one of my favorite works of hers is the novel The Hearing Trumpet, which stars the 92-year-old Marian Leatherby and her fantastic adventures in a nursing home. It’s been described as an “occult twin to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” but if you squint (hard), it could also be a Surrealist, occult Golden Girls. At least, it has the same sense of madcap fun with one’s pals, whatever the rest of society thinks about older women. Carrington was only about 40 when she wrote it. For such a witchy feminist, it makes sense that she wrote a book centering older women coming into their magical power, pushing back and breaking free. Once, when Moorhead asked what Surrealism meant to her, she said: “It’s the belief that nothing is ordinary; that everything in life is extraordinary. And being old is no more, no less, extraordinary than being young.”

Ultimately, though, Carrington did not identify as a Surrealist. She eschewed all labels that ended in “ist.” The only possible exception, according to Moorhead, was “feminist.” Carrington once told a friend, the Mexican journalist Elena Poniatowska, that her favorite date in history was one that hadn’t happened yet: “the fall of patriarchy that will take place in the 21st century.”

Perhaps this is part of what’s helped her work to rise recently, too—she was always looking ahead, to a world of care and interconnectedness, ecology and spirituality, that could flourish even as the world’s institutions crumbled and burned. As someone who fled fascism, the problems of 2025 would seem deeply familiar to her, I suspect. But I also think she would be thrilled by the pockets of joy, creativity, and freedom that we’ve managed to carve out, and she would urge us to work to keep enlarging them as part of the path forward. ◼︎

Bess Lovejoy is the author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses and Northwest Know-How: Haunts. Her non-fiction has appeared in The New York Times, Lapham’s Quarterly, Atlas Obscura, and elsewhere. Her fiction has appeared in The Ghastling, Happy Reader, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. She lives in Seattle.