More Paint

Brandon Bye’s eerie and empathetic visions of the “other Seattle”

More Paint

Brandon Bye’s eerie and empathetic visions of the “other Seattle”

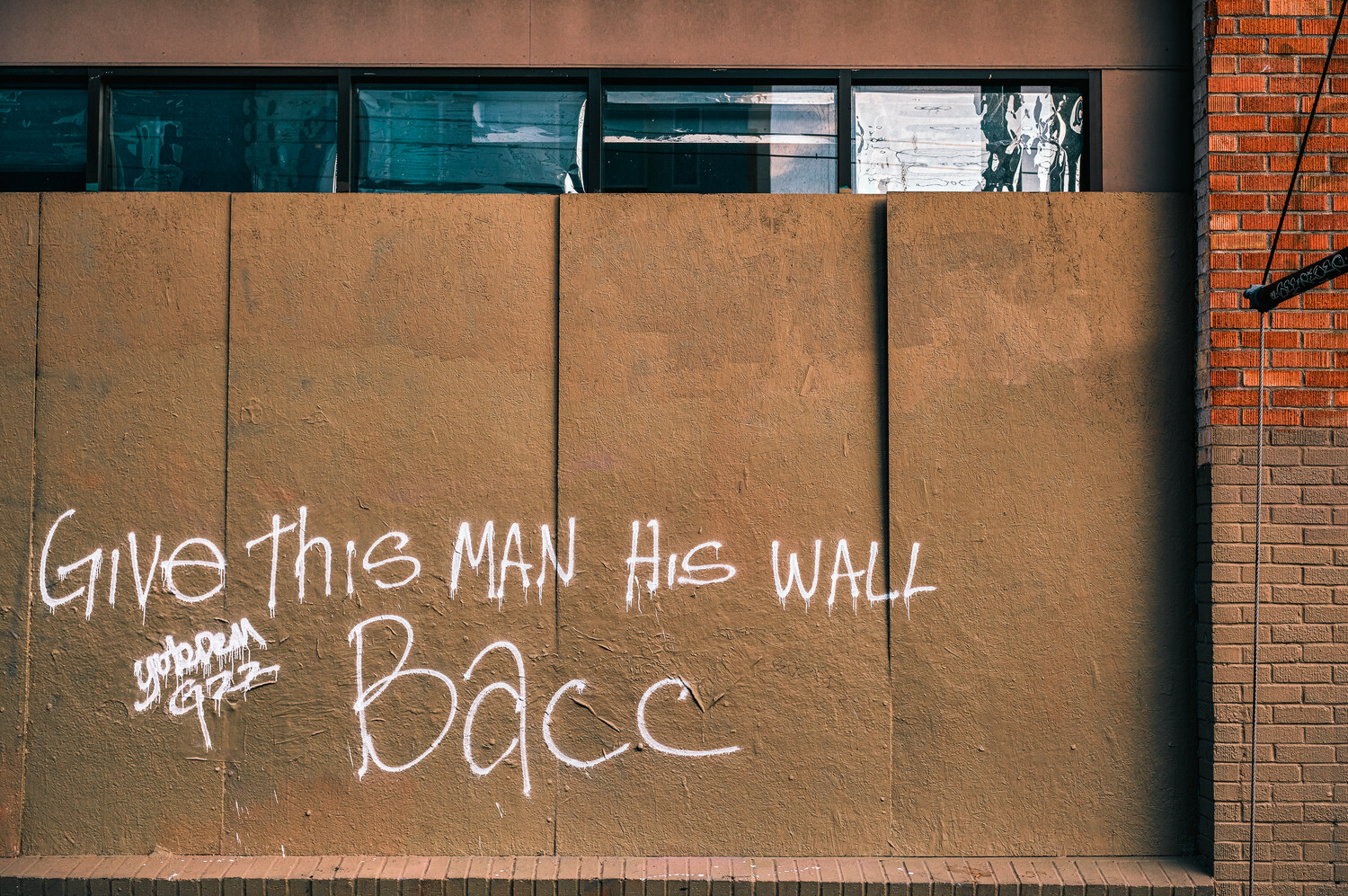

Brandon Bye’s photography is both deeply intimate and intertwined with Seattle—a twisted relationship with a city that feels unwell.

Bye has been documenting pockets of South Seattle, where he lives, for the past three years. His exhibit, More Paint (opening today at Base Camp 2), showcases the result of that work: a collection of images that weaves its way through graffiti, cover-ups, the streets, and those who live on them, capturing cinematic, unsettling, and unforgettable images.

The photographs are haunting and seductive. Rich, pulsating color brings a profound presence to areas often unnoticed and uncared for. Some images are painful, hard to digest. Don’t look away, Bye seems to be saying: This “other Seattle” is our city too. What stands out most in Bye’s work is a sense of empathy: his is not the eye of a voyeur, but a lens through which to see the city with appreciation, and to linger on things many refuse to view at all.

The exhibition of Bye’s work coincides with the release of a book of photographs by the same name, published by another luminary from the Seattle photography world, Nate Gowdy. I sat down with Bye, Gowdy, and editor Lisa van Dam-Bates, for a conversation about Bye’s process, graffiti, Seattle, and Vietnamese cakes.

JAKE MILLETT: Was there a specific galvanizing moment when you realized that this work is important, that you wanted to share it with people?

BRANDON BYE: There were so many moments. The galvanizing moment, the one that shifted things into sixth gear, I was in Buenos Aires in December of 2023. I had gotten laid off from Amazon. It was the best day of my year. And I was like, okay, fuck it. I booked a one-way ticket to Buenos Aires. There is a bunch of graffiti all over that city, and there was one artist who wrote, “no me baño” on the walls. It was just everywhere, like every neighborhood.

MILLETT: And that means “I don't bathe”?

LISA VAN DAM-BATES: “I don't bathe myself.”

BYE: Those words were always behind people living on the streets, so it felt intentionally political to me. When I got back to Seattle, I just saw the city differently. I saw a link between graffiti and life on the streets; I didn't quite know how they were related, but it felt like they were. In another moment, I was driving back from West Seattle, where Spokane meets Airport Way. I pulled over to photograph a piece of graffiti from an artist named TERU. The graffiti and the atmosphere in the jungle really had an effect on me. That was a moment where I started to connect the dots between homelessness and graffiti, and then in Buenos Aires, that was when it was like, holy shit, these things are part of the same story. Then as we started thinking in terms of a book, the writing began to clarify the connection for me.

MILLETT: So when you go out shooting, are you always carrying a camera with you for when you encounter that moment, or do you go out more intentionally to shoot?

LVDB: I’ll just say that when walking around with Brandon, he does not carry his camera around with him, and every five minutes, he's like, “that's a photo. That's a photo. That's a photo.”

BYE: Yeah, I used to carry my camera around all the time, but my process has changed a lot over the two years spent shooting this book. It started out more like exploring, like being a kid on a bike going around and like, you know, going to rope swings and convenience stores, just hanging out. The equivalent of that is going to SODO and walking the train tracks, or hanging outside gas stations and having weird interactions with people.

MILLETT: I know what you mean about that joy of creating, like you're a child and just letting go.

BYE: Exactly. And with the production and presentation of the book, I've got to be an adult about this, you know, and I'm like, I just want to be a kid on a bike with a camera.

MILLETT: The art admin side is important for the career of an artist, but it's not the same as the creating.

BYE: Definitely not. And don't even get me started on social media.

LVDB: We're working on it!

BYE: I took a photo when I was out brooding with a cigarette.

LVDB: Thank you.

BYE: But I'm like, this is a phone photo. I can't publish this shit.

LVDB: It's your social media.

GOWDY: Apple paid my buddy $10,000 for a phone photo. I'm just saying. It was on the back of the New Yorker.

MILLETT: Your work feels deeply connected, entrenched in the fabric of the city. Some might say the “underbelly” of the city. How would you describe your relationship with Seattle?

BYE: I was about to leave. 2024 was just sort of a wear, and I didn’t know what I was doing around here. I traveled a lot in 2024, and when I came back, I was like, I don't know if I like this city. The way that people interact with each other here is not normal—or rather the way they don't interact with each other. I could sit at Gas Works Park for 10 straight days and no one would come talk to me. I could sit at the park in New York for 30 minutes and I'd have like five pretty interesting conversations, you know? So I was like, I'm out of here. Fuck this place.

But two things happened in the making of this book. For one thing, the whole time I've lived in Seattle, since 2008 it was pretty much South Seattle. But photographing the city has given me a sense of pride for this place, because I know it really well now. This project has caused me to think about the civics of this place, about the social dynamic of this place, in a deep way. Even if it's a little jaded, the experience has given me a little bit of pride for this place. So now I'm like, You know what? Fuck this place, but it's mine. A kind of ownership. Or maybe not ownership, but a belonging. I feel like I've engaged with this city so much that I belong to it.

MILLETT: So, as Nate touched on, you have traversed different mediums throughout your career. Can you take us on a little journey?

BYE: Writing is the worst one. Writing sucks.

MILLETT: Ha!

BYE: I actually went to school for creative writing, and have been a writer in one way or another for the past 15 years, it’s how I've made a living.

LVDB: I think that kind of unites us too, because Nate originally comes from journalism, and my partner and I founded an alt monthly when we lived in Austin.

GOWDY: We all started as writers.

LVDB: And I have done a lot of graffiti. It's funny to have that kind of overlap.

BYE: Yeah, we all have a bit of a writer’s mind, so that's been a connection point. Then I made music and did bands for a while, until the pandemic stopped that. But I kept writing instrumental music and got way into writing cinematic instrumental music, which we’ve actually used in the promotion of this work.

MILLETT: The photos feel very cinematic. Are there any specific graffiti writers that you have a special affinity for?

BYE: I think the ones I have an affinity for are the ones I’ve had conversations with. Like this couple—they have amazing names, like movie script names—Casket is the girl and Satn is the guy. I ran into them a couple times, and I like both of their styles a lot. Casket uses a calligraphy style that I dig, and Satn's style changes a lot: it's not neat and perfect. It's pretty, like, I don't know, carved in. Another shout out goes to Blink. His name is Bill. He's probably most known as the hot dog guy.

MILLETT: Love hot dog man!

BYE: I connected with him early on. He did some artwork for the book that didn't end up making the cut, because the book went in a different direction. But he's a really cool guy and he's been a writer in the city forever, and it was awesome to talk to him about the heritage and lineage of graffiti writers around town. I don't have any idea who Clepto is, but I like his work because it's just prolific, and he's been doing it for a long, long time. That's the cool thing about graffiti writers: these people are artists and they're not just doing this because it's trendy or because it's some random thing they’ve taken up. Not like "I'm going to go to a knife-making class" or whatever. They're doing it because it's a part of their identity, and I respect that so much. Also, I just think the letter “C” that he writes is always cool. Sometimes he just does the C.

MILLETT: Tell us about living and working in South Seattle.

LVDB: I feel like South Seattle is this little bubble where like, it is a real city, and it's so different from the rest of Seattle, the white Seattle that we kind of like internalized as being “PNW.”

BYE: Yeah, no one in South Seattle or SODO is walking around with a matcha latte and a stand-up paddleboard.

LVDB: I see Brandon existing in this area in a very different way than most people are existing in the city at large.

MILLETT: Favorite takeout in the South End?

GOWDY: I was going to bring that up! Brandon is always saying, “I know this great place in the South End.”

BYE: The first two places that come to mind are two Vietnamese spots: Q Bakery. That place rules. And Tony’s is across the parking lot.

LVDB: Is that where you get the baguettes? Brandon’s always bringing baguettes around!

BYE: Yeah, those two spots are awesome. I haven't got a cake yet from Tony's, but maybe there will be an occasion. Maybe we should get a cake from Tony's to celebrate the launch of this exhibition.

GOWDY: No wine and cheese at this show...

BYE: We're getting a Vietnamese cake.

LVDB: It’s going to be Steel Reserve and a fancy cake.

MILLETT: Hell, yeah! ◼︎

Jake Millett (b. 1988) is a born and raised South Seattle multidisciplinary artist. Find his work here.

More Paint is on view at Base Camp 2, located at 1901 3rd Ave, through July 26.