Spirit House at the Henry Art Gallery Makes Room for the Living and the Dead

There’s a detail you might not notice when you walk into Spirit House at the Henry Art Gallery. A small, tangerine-colored butterfly perches on Greg Ito’s sculpture, The Weight of Your Shadow, near the entrance. The butterfly rests atop a blue shack, a part of the sculpture reminiscent of the barracks where Japanese Americans—such as Ito’s grandparents—were incarcerated during World War II. More tangerine butterflies trail up the wall and into the nearby antechamber, then flit away toward the bigger rooms of the exhibition. Each room is organized around one of the show’s themes: Ghosts, Hauntings, Shrines, Dimensions, and Spirit Houses.

Amid the genre-defying, phantasmagoric artwork—all made by artists of Asian descent primarily working in the US—it’s easy to overlook the butterflies. But they’re not just a cute decoration: They’re citrine messengers, part of Ito’s art, and a clue to some of the primary ideas animating the show.

Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, associate curator of modern and contemporary art at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center (where Spirit House originated), explains the meaning of the butterflies by relaying a story from Ito. The artist was close with his grandparents, Alexander tells me in a Zoom interview from her home in the Bay Area, but when his maternal grandmother died, he couldn’t make it to her funeral. The day of the ceremony, Ito was walking through Golden Gate Park thinking about his grandmother when a butterfly landed on his hand, then his face. The creature spent what Alexander calls “an inordinately long time” with Ito. He felt it was a visit from his grandmother’s spirit. When Ito called his mother to tell her the story, she revealed that his grandmother’s family mon, or emblem, is a butterfly—something he hadn’t known until that moment.

“A lot of people would maybe dismiss that or call it a coincidence,” Alexander says, “but I think that you can take these events seriously and look at what happens if you do. You might end up learning something about your family that you didn’t know before.” It’s just one example of how the show foregrounds “inherited, embodied, and psychic forms of knowledge,” in Alexander’s words.

Alexander, who co-directs the Asian American Art Initiative at the Cantor, says her impetus for the exhibit grew out of years of studio visits with artists in the Asian diaspora. Many of them were making deeply personal work about family histories, migration, and memory. “A lot of work was about intergenerationality,” she says. “But when you think about family, you have to think about death, and you have to think about that long passage of time and [people’s] spiritual orientations toward it.”

From those visits, a pattern began to emerge: the willingness of the work to occupy the space between the tangible and the intangible. The idea of the spirit house became Alexander’s organizing metaphor. In Thailand, where she was born, spirit houses are a common sight: miniature shrines outside homes and businesses where offerings are left for ancestors and local spirits. “Every work in the show is not literally a spirit house,” she says, “but I think of them as these portals to different places … places where you can leave offerings to the dead, places for you to think through difficult topics.”

Korakrit Arunanondchai’s Shore of Security—located in an antechamber festooned with butterflies—is the only work in the show that directly references a Thai spirit house. Fashioned in part from blackened pieces of a dollhouse that was originally created by the artist’s mother, the work glows from within, lights softly pulsing like some long-gone ancestral hearth. It’s meant as a testament to the ability of art to cross realms, Alexander explains in the exhibition catalogue—the way that both art and spirit houses can transcend physical limits and serve as mediators of family memory.

In a far different mood, Do Ho Suh’s candy-colored Doorknobs: Horsham, London, New York, Providence, Seoul, Venice Homes gathers cast replicas of the literal door handles the artist has touched across his many homes, distilling the intimacy of a gesture repeated thousands of times into something both personal and archetypal. It’s another example of how supposedly inanimate architecture can hold a key to intimate memories and emotions.

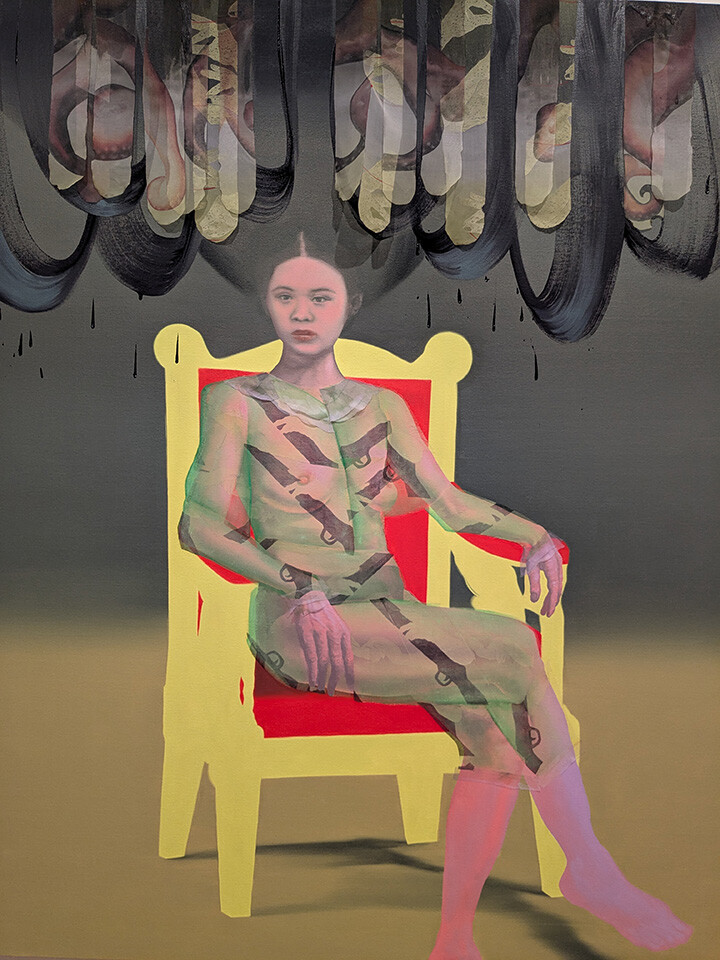

Like Suh’s doorknobs, other works in Spirit House hold memory in physical form, but with a spectral charge. In the Ghosts section of the exhibit, pieces “chase ghosts—the ungovernable ancestral lacunae of diasporic life,” as the catalogue puts it, offering spaces for otherwise impossible reunions. Lien Truong’s six-foot oil painting The Crone, which takes up much of the back wall in this section, springs from a single image: the only surviving photograph of her paternal grandmother, who died young during the French occupation of Vietnam. Truong never met her, yet the portrait’s presence fills the gallery with her commanding stare.

+++

The Crone rewards deep looking: the translucent lime-colored fabric that sheathes the central figure’s young body is painted with both clasped hands and guns, and strips of silk that hang from the top of the painting are illustrated with curling octopus tentacles, a nod to her family’s eventual migration across oceans.

Kelly Akashi’s Life Forms (Poston Pines) and Inheritance, meanwhile, feel like artifacts from another realm. Each features the artist’s hand—cast in bronze and crystal—holding fragments gathered from the former Japanese American detention camp in Poston, Arizona, where her father and grandparents were incarcerated during World War II. In Life Forms, a bronze hand cradles a pine cone and twig from trees likely planted by detainees—living markers in a landscape stripped of structures, holding memories of Akashi’s ancestors. In Inheritance, the crystal hand, adorned with Akashi’s grandmother’s bracelet and ring, refracts light, as if passing memory from object to viewer.

Hands emerged as an unplanned motif of the show, one that surprised even Alexander. “These artists were all thinking through hands—these bodily points of connection between yourself and others, but also thinking about care and making and tools.” In Cathy Lu’s Banana Tree (part of the Shrine section), a primordial hand reaches up from a gleaming stack of overripe bananas studded with sticks of unlit incense. A frequent shrine offering, incense is often meant to honor the deceased and act as a bridge to the spirit realm, carrying prayers on its smoke. The hand is a representation of part of the Chinese mother goddess Nüwa (or Nügua), who is said to form people from clay—a fitting subject for a ceramicist. Like oranges, which also recur in the show, bananas are common offerings on shrines in Asia, and an allusion to a racist metaphor for those who have “betrayed” their Asian identity.

Yet hands here are not just symbols of labor, craft, or reaching across worlds. The hands motif reoccurs within Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s sculptures Nothing Ever Dies and Nothing Is Ever Lost, Nothing Ever Gained. Part of the Hauntings section, both sculptures are formed from brass artillery shells that the artist sourced from Vietnam’s heavily bombed Quang Tri province. Nothing Ever Dies is a singing bowl tuned to a specific frequency that’s said to be healing; Nothing Is Ever Lost, Nothing Ever Gained takes the form of the arms of a bodhisattva making the abhayamudra, a gesture meant to dispel fear and signal reassurance. Both are reminders that hauntings are not just about spirits—here, they are also about the afterlives of war, migration, and displacement.

Some works in Spirit House make the unseen explicitly visible. Binh Danh’s chlorophyll prints on leaves preserve ghostly images within the delicate tissue, as though nature itself were holding the memory—an echo of the pine cones and twigs that Akashi collected. Danh’s The Botany of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum #1 and #3 depict unidentified victims who were tortured and executed by the Khmer Rouge at the Tuol Sleng prison, from whose archives Danh retrieved these photographs. Danh has said that he hopes that, when viewers look at these works, “the dead are able to live for a time in our minds and be part of the material world.”

In this way, artists—and those who experience art—become spirit guides. Art becomes a way of accessing challenging topics that many in the Western world shy away from.

“I wanted this show to be about not just art but the most difficult questions and existential quandaries that we all face,” Alexander says. “It’s grounded in the experiences of belonging to an Asian diaspora, but really, my hope was that life and death are the things that we can all relate to.” Alexander speaks candidly about the differences she has observed between the Western and Thai approaches to mortality. “When I moved to the States,” she says, “our attitudes toward death and the afterlife… people just didn’t want to talk about it. Or it became this very scary thing. Versus when I was growing up in Thailand, when you interact with spirit houses all the time, you are also thinking about the dead all the time.”

And while the dead in Western culture often feel frightening, many of the representations here are bound by a thread of love that weaves through ancestral and living communities. Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya’s What Remains, part of the Dimensions section, honors the matriarchs in northeastern Thailand who taught her how to make traditional chok fabric. The rich, almost blood-red chok streams down behind boxes used to store sticky rice, a reference to the women’s labor in the fields. Golden hands, cast from women in the diaspora and meant to symbolize the compassion of various Southeast Asian goddesses, reach out from the containers, while beads variously resembling pearls, rice, and tears fall through their fingers. It’s fitting that What Remains is one of the last works you experience in the show, since it sums up so many of the themes: ancestral knowledge, honoring and reckoning with the past, and the capacity of art to cross realms to heal. ■