The Barbara Earl Thomas’s High-Frequency Art Method

On a weekday in Seattle’s Columbia City neighborhood, a few blocks from Genesee Park, Barbara Earl Thomas is at work. Downstairs, in her home studio—both workshop and base camp—the air hums with sound. Sometimes Beyoncé, sometimes an audiobook. The long tables are crowded with the tools and materials that fuel her practice. X-Acto knives. Tyvek. Rolls of colored paper. On the walls, photographs of family and friends are mixed in with designs for glass vases called “story vessels” and a constellation of images cut from magazines—photos of people, animals, and plants that inspire or that she has included in her works.

In one corner, sheets of Tyvek lean against the wall, already scored with the beginnings of a new cut. Tyvek is what Thomas uses for many of her larger installations. It’s a building material that looks like white fabric but feels like reinforced paper. You may have seen it wrapped around construction sites or houses. Yet Thomas, blade in hand, carves silhouettes from this crinkly, sometimes slick industrial material that’s designed not to tear. Light pours through the windows, spilling across the arcs of her cuts. Toward the back of the studio is a beautiful outdoor area: a secret garden, almost entirely canopied by trees and plants.

This is not chaos. It is a workshop of deep discipline. Thomas is here six days a week. From her studio, she hosts studio tours, fields calls from museums, drafts architectural proposals, meets with fabricators, and still makes time to sharpen her blades and her ideas. Her presence is buoyant and gracious. She has a quick wit, and when she laughs, it comes from somewhere deep. The seriousness is there too, braided into the joy. She is not performing balance; she is living it.

“Making is thinking for me,” Thomas says, and this philosophy runs through everything she does, from the most intimate portraits to her largest public installations. Growing up in a household where necessity bred creativity, she learned early that “If you needed something, you made it.” This problem-solving mindset would become central to Thomas’s art practice, where making is always a response to life’s challenges and opportunities.

As a multimedia artist, Thomas has spent decades refining a craft and practice that moves easily from egg tempera paint and cut paper to blown and sandblasted glass and large-scale public works of iron and steel. Each medium is a different register of the same language. You’ll see Thomas’s recent local public works installed at Judkins Park station, which Sound Transit has slated to open in early 2026.

This fall, Thomas’s work leaps to an entirely new register. On September 6, she unveiled The Iron Gate in Nantes, France, one of Seattle’s sister cities. Just three weeks later, she will celebrate her curatorial debut in Europe with the opening of Jacob Lawrence: African American Modernist at Kunsthal KAdE in Amersfoort, Netherlands. It will be the first time Jacob Lawrence’s work has been the subject of a solo gallery presentation in Europe—a glaring oversight to those familiar with his legacy. The show will include Thomas’s own portraits of Lawrence, her dear friend and former professor, creating a conversation between student and teacher that spans decades. Together, these shows signal that Thomas is no longer just a locally—or even nationally—known artist. She is working on an international scale, exemplified in particular by The Iron Gate.

Thomas’s design for The Iron Gate began with research in Nantes during June of 2024, where she met with city officials, walked the park’s pathways, and absorbed information about the native plants and botanicals of the site. This process introduced her to the complexities of French public art contracts, a process she jokes has made her an accidental expert. She returned to Seattle with a sense of the garden’s rhythms and its connection to her own city. The work, an architectural gateway that transforms an entrance into an encounter, was commissioned for Parc du Grand-Blottereau as part of the Jardin de Seattle à Nantes project, celebrating forty-five years of the sister city partnership between Seattle and Nantes. The site is more than a garden: It’s a landscape infused with the spirit of a food forest, drawing inspiration from agricultural traditions that have also taken root in Seattle.

The collaborative process revealed Thomas’s methodical approach to public art. Working directly with fabricators, she engaged in speculative modeling, examining the wooden prototypes to test the scale and gauge of the gate design. Thomas, always one step ahead, was nearly finished with the design for the piece by the time she received the contract. This is how she works: backward from the desired impact, with the discipline and foresight that comes from decades of serious practice.

The gate stands nearly ten feet tall, cut from weather-resistant COR-TEN steel. It functions as both threshold and narrative surface, a story carved into metal. Intricate patterns weave together human figures, lush flora, and hands reaching across space. Birds flitter around groups of hanging orbs resembling apples, while words in English and French dance through the scene. Like many of Thomas’s works, this piece surprises with hidden figures and secret words skillfully woven into patterns. It rewards close looking and holding attention through discovery, and it invites curiosity.

+++

Thomas’s artistic influences span continents and centuries; from Albrecht Dürer and Austrian Expressionist painter Egon Schiele to more contemporary storytellers like Jacob Lawrence and Kerry James shall, who use artmaking as an emotional reaction to the turbulent times they’ve lived through.

In The Geography of Innocence, a major solo exhibition at Seattle Art Museum in 2020, Thomas tenderly depicts Black children as both an endangered group in the face of American social and political violence as well as a beacon of hope for the future. The interplay between the stark black cuts and the vibrant colors beneath creates a visual language that’s both beautiful and unsettling, melancholic and hopeful. There’s something about that emotional urgency, the sense of being rooted in a specific moment while speaking to universal human experience, that is connected to Thomas’s artistic concerns.

“My work is about touching the moment you’re in,” Thomas says of her portraits. “We don’t know what it means to history’s grand narrative, but my visual notes, which are the work, are to document the everyday and how we survive all the small hits.”

Thomas’s work has found its way into major collections around the world; her pieces travel now as far as she does. Comparisons to other artists may come to mind: Ebony Patterson’s intricate designs meant for slow looking, Bisa Butler’s magical fabric works, and Derrick Adams’s striking color-filled portraits. Like her mentor Lawrence, she has a gift for distilling multiple narratives into a single image. And like him, she doesn’t make declarations so much as invitations. The viewer enters the work through a gesture, a pattern, or a repetition that feels like something remembered from long ago.

Light is also an active participant in Thomas’s practice. In her studio, light moves through the openings she’s cut into Tyvek sheets and pours over the papers beneath, changing their tone and temperature. One moment, the light makes a piece feel expansive. At another angle, the light can make it collapse on itself. She uses this mutable quality to keep the work alive. A single piece can meet a viewer differently on two separate days.

+++

Thomas met Jacob Lawrence in the 1970s when she was an art student at the University of Washington. At the time, Lawrence was already a world-renowned artist, known for his Cubist paintings that depicted figures of Black American history as well as scenes of everyday life in the United States.

“Jacob arrived in his mid-fifties and was one of two Black professors in the art department,” Thomas says. “Unbeknownst to me, he was already famous. I did not come to our relationship in awe but rather as a young person meeting a new professor.”

She met Lawrence with curiosity and intelligence. He met her with rigor. He taught her to be clear, focused, and intentional in her approach to her own work. “He made me work hard, and like it,” Thomas recalls. “He’d say, ‘If it doesn’t serve the composition, get rid of it.’ Or ‘Barbara, if you’re going to use that pattern, investigate its structure. There is no pretending. Draw it again until you are fluent.’ So I went back to my drawings again and again until I could render the anatomy of the body or the landscape. I came to think of Jacob’s instruction as life lessons—a way to move through the world with truth.” These directives stayed with her through her artistic practice.

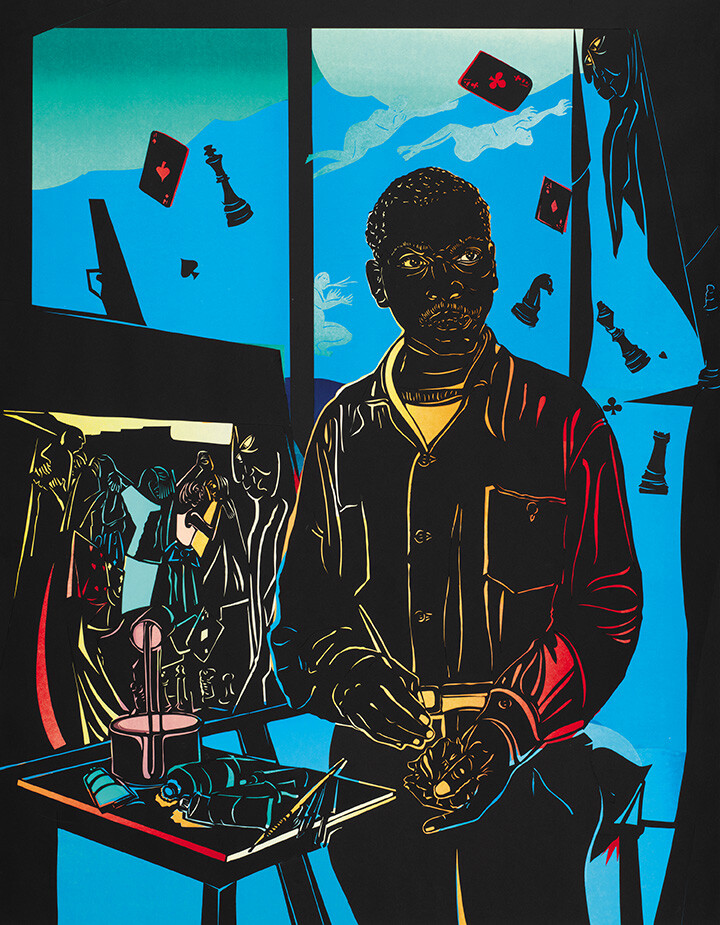

Thomas, who curated the Amersfoort exhibition of Lawrence’s art, also has four of her own works in the show; she chose to depict four distinct moments that span Lawrence’s life and career, from his early days in Harlem workshops to his later years as a teacher in Seattle. Rather than create literal portraits, she builds environments around him, incorporating elements like chess pieces and playing cards lifted from his own paintings, architectural details from New York City, where Lawrence lived and worked for forty years, and the tools of his trade: paint tubes and brushes. Her approach is archaeological, reaching back to capture not just Lawrence’s physical presence but the creative atmosphere that surrounded him.

Through each portrait, Barbara creates a visual conversation between past and present, using symbolic elements and carefully chosen backgrounds to show how place, time, and creative community shaped Lawrence as both artist and teacher. She depicts his steady gaze meeting the viewer; when he looks back at us, we become his students too.

Since their first meeting at UW decades ago, Thomas’s relationship with Lawrence deepened beyond teacher and student, and she became like family to him and his wife, the artist Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence. Even after her school years, Thomas remained a close friend of the couple and was there for them through the end of their lives.

The most moving piece in the show is a portrait featuring two cut paper figures in the foreground, backlit by layers of vibrant hues that seem to hold their own light. They both stand, smiling through negative space, captured in a pose that reveals their loving connection across time. It’s a portrait of the Lawrences. More than homage, it’s a testament to how deeply loved they were, seen through the eyes of someone who knew them not just as artists and mentors, but also as family.

The Amersfoort exhibition is the first of its kind to center Lawrence as a modernist innovator whose compositions and color sensibilities rival any of his contemporaries. It is not a retrospective but a gallery presentation, which opens him up to European markets and audiences in a way that has never been done before. The show places Lawrence as a central member of the modernist canon, an overdue recognition for an artist who would have been 109 when this historic exhibition opens.

+++

The Iron Gate will remain in Nantes for decades, gathering ivy, weathering, becoming part of the park’s life. The Jacob Lawrence show will have a shorter run, but the impact will be just as long-lived, introducing new audiences, collectors, and critics to one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century. Thomas’s superpowers lie in turning ambitious ideas into tangible reality. While she navigates a complex web of responsibilities across continents and time zones, balancing emails with French fabricators and shipping logistics for the Lawrence exhibition, she never loses sight of her mission. As this new audience looks closely at her work, they will catch glimpses of details and stories that have taken years to perfect.

This is how art moves through the world: in high frequency, encounter by encounter, person by person, until an idea moves to a studio and then becomes part of how we see ourselves.

Thomas returns to Seattle knowing she’s planted something permanent in European consciousness. The work she makes next will reach audiences who already understand what she’s capable of. The blade is sharp. The light is perfect. Barbara Earl Thomas is an artist moving in full stride. ?