Ekphrastic: Gabrielle Bates

On Hayv Kahraman’s Look Me in the Eyes

Ekphrastic: Gabrielle Bates

On Hayv Kahraman’s Look Me in the Eyes

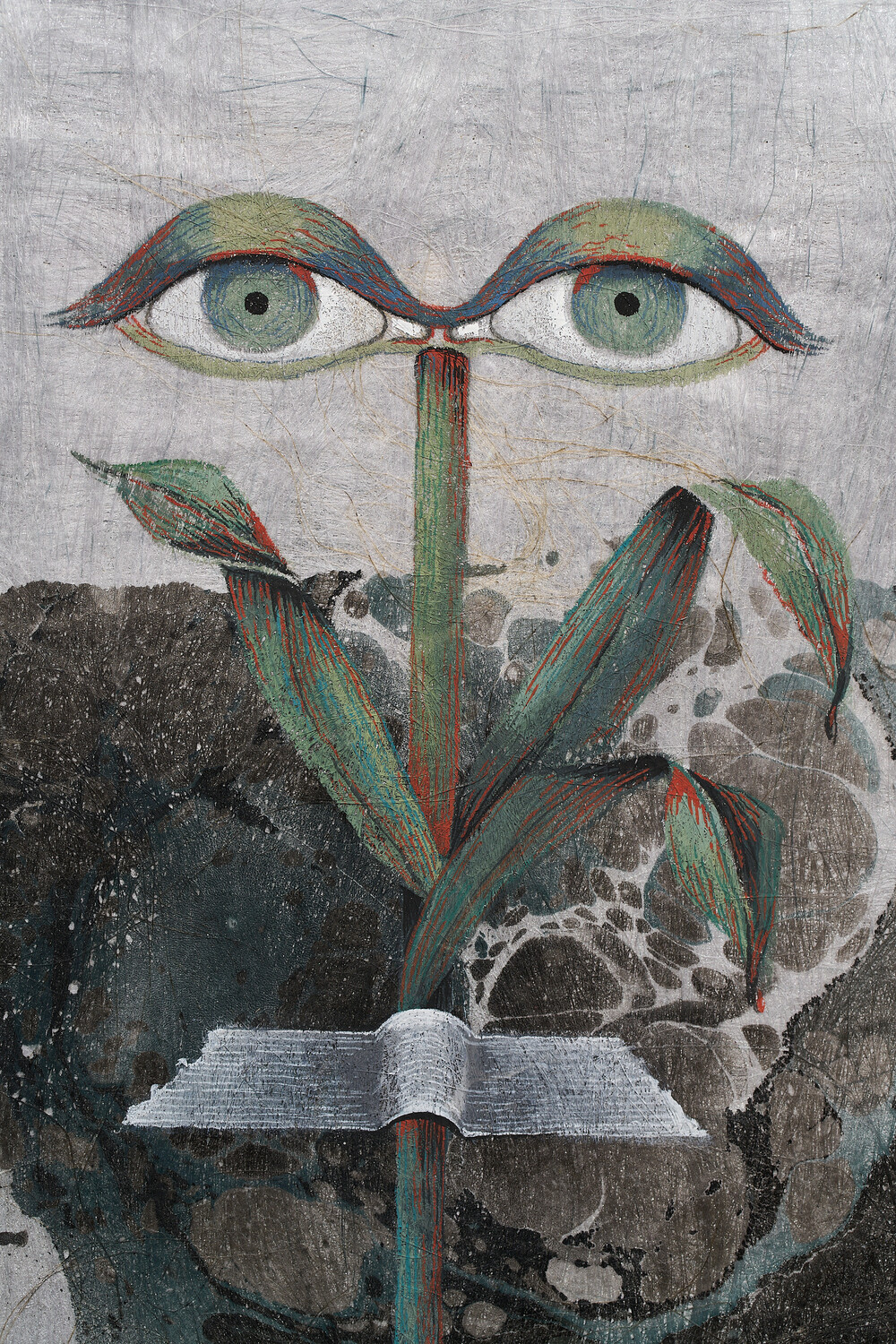

“All the artists I love most engage with the “collaboration” of looking. The moment when what we see appears to see us back. The inter-penetration of perception: People looking at other people, at animals, at a hand, at the painted hand on canvas, and the moment where all this looking at—one directional, solitary—becomes instead a convergence, storm front, waltz, wrestle, sex. The convergence is both a moment and a place. It is an ecotone in time. Impossible, improper interminglements of flora and fauna: defining of the “grotesque,” in its beginnings. In poems, in paintings, a feminine grotesque calls to me again and again.

Writing is a form of reading. Painting is a way of looking. When we look at a painting with sustained attention, we are sometimes said to read it; I think that if we look long enough at an image, and are lucky, we are read to. Someone or something reads to us about consciousness and light. What text is being read? I think it predates any language we may have studied or grown up speaking.

What does it mean to carve with an eye? What does it mean to twist an eye off a vine or pry from a vine, with your finger, a finger? What does it mean to harvest while reclined, barelegged? Do new eyes grow from the eyes of the dead? Will she taste the eye she picks? Will she break the finger she bends? Will she eat it? What does it mean to swallow an iris? How far do the reverberations go before they hit the silence that gave them birth? The kingdom of plants is kingless. Many millions of years before ears evolved, there were mouths and eyes.

The hands touch palm to palm along the vines. Elsewhere, the hands point. Elsewhere, the hands make a shape that’s meant, colloquially, to say, “Fuck you.” Rain falls, ancient and hypercontemporary, on the museum roof. It soaks my coat while I walk home. I blink it and taste it and wear it and walk on it. This is the season of secret lives feeling for their edges, the season of expanding night. Women come to me in dreams and we outline each other’s bodies with our mouths in the romantic echo of a crime scene. There are creatures that could not be in trees in trees.

The enemy of dreams is not interpretation but explanation. Interpretation is hospitable to life; explanation poisons the water. “A poem must be experienced, not decoded,” the poets beg. The painter is able to dislocate her shoulder and thigh bone; she says, “I found refuge in this freakery.”

I used to draw eyes on everything. When I was fifteen, my first boss found the habit so disturbing, she called me into her office. She’d known another girl who drew eyes, and that girl hadn’t turned out so good. After three days of surveillance, she remarked on the eyes I drew as well as the ones in my head. “You’re too young to have those dark circles,” she said, as if demanding I peel them off and hand them over to her.

I am alone in the room, surrounded by eyes. Circling counterclockwise, I read the paintings along the blue wall, listening. Each image presents the near-symmetry of vines. The painter says, “Near, but not quite, self-portraits.” The eyes of the women look differently for being irisless, but they still look. What they see is what I see, but from an angle that does not exist here. Surveillance in this place is embodied, human, possible to encounter, flesh to flesh. I am separate from it, invited to approach. When I am “seen” by the painted eyes, I feel the hairs on the back of my neck. The power of sustained, blinkless looking. The curse of sustained, blinkless looking. The gendered role, the job, of weeping. A water that climbs up walls. Any piece of art—painting, poem, film—that has ever meant anything has been disobedient to something. The images demand “See us” less than they level the claim “We see you.”

With increasing regularity, I think about how vital the poetic image, or deep image, seems to be for me, personally, understanding it to be a kind of counterforce. To the chaotic inundation of our current technological epoch, designed to provide maximum hollow spectacle and minimal collaboration, thereby keeping us “useful” and “safe,” any image with which we can meaningfully entangle, any image of true disturbance and depth, offers defibrillation of the spirit. A branch of lightning in slow motion. Inflorescences of hands. Whenever I see marbled paper, I remember the technique requires a literal collaboration with water—a physical analog for the spiritual mystery that art-making at its most valuable always requires.

Looking makes us vulnerable, permeable, subordinate; it risks. Mutual looking is humbling, troubling, a rush. What’s seen doesn’t belong to the eye any more than water belongs to the stem of a plant. Of a deep image, there is no sole custody. Its warnings are jointly warned; its promises are jointly promised. But looking belongs first to what is looked at; to look—to truly, deeply look—is to live for a look’s duration at the mercy of what you see.

A true look cannot be translated into language with any exactness, but it is always closest to a question.

Ekphrasis is a Greek word meaning "description" or "interpretation." Ekphrastic poetry is a literary device by which the writer responds to a visual work of art through use of vivid description, extending the experience of an artwork into the realm of language.

Hayv Kahraman was born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1981 and now lives and works in Los Angeles. Kahraman’s art work, informed by her upbringing as an Iraqi/Kurdish refugee in Sweden, has been featured at CAM St. Louis, the Joslyn Museum of Art in Omaha, and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, among many other venues. Look Me in the Eyes, her largest solo exhibition to date, is on view at the Frye Art Museum until February 2025.

Gabrielle Bates is the author of Judas Goat (Tin House, 2023), an NPR Best Book of 2023, a New York Times Book Review Critics Pick, and a finalist for the Washington State Book Award in Poetry. Originally from Birmingham, Alabama, she currently lives in Seattle, where she works for Open Books: A Poem Emporium, co-hosts the podcast The Poet Salon, and teaches occasionally for the Tin House Writers’ Workshops.