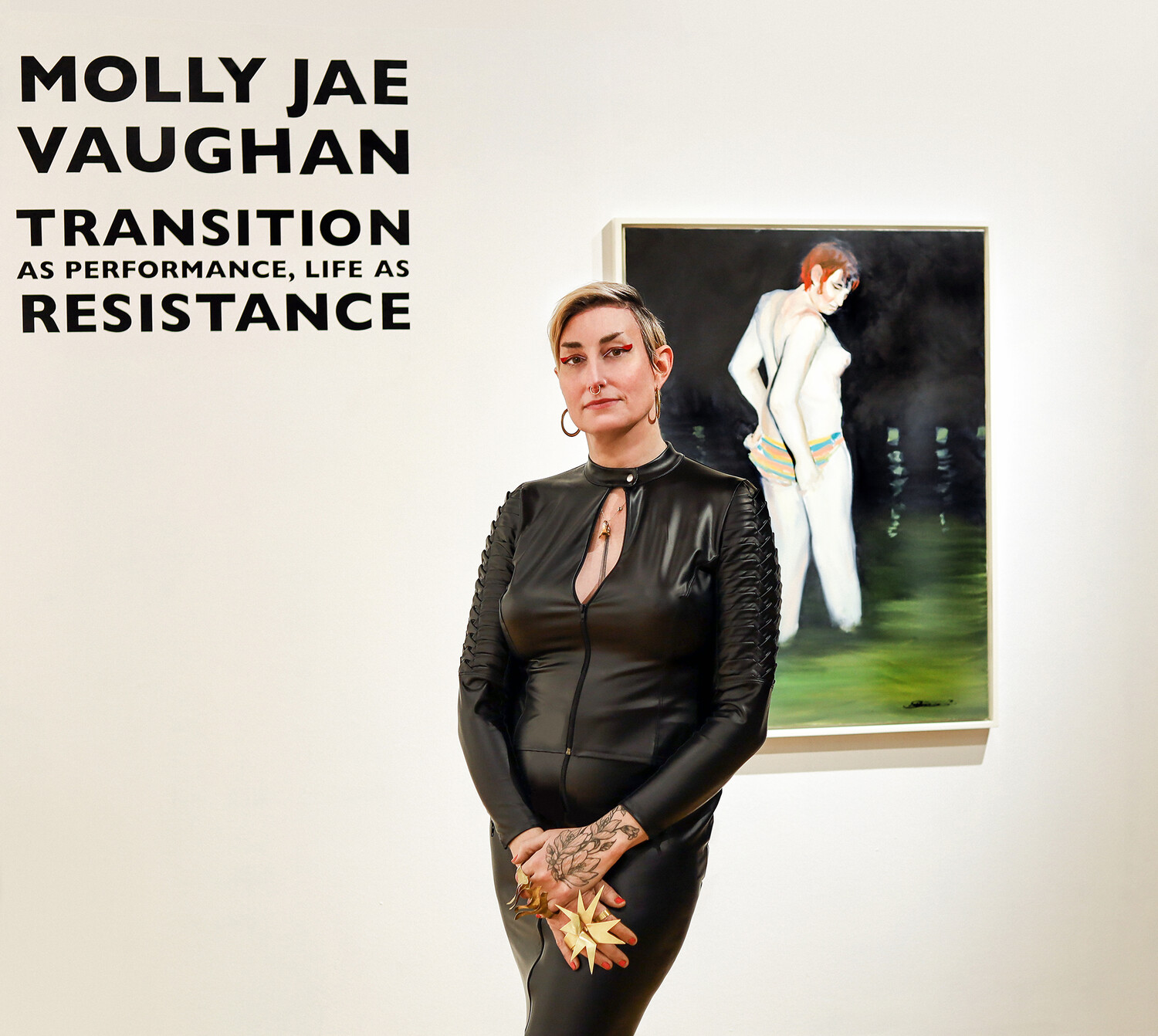

Molly Jae Vaughan

Transition as Performance, Life as Resistance

Molly Jae Vaughan

Transition as Performance, Life as Resistance

The video opens on an empty cement platform, stage-like, in front of a nondescript building. The sky is grey, and clouds swirl slow patterns across the screen. If you’re from the South, you know this type of day. Looks cold but isn’t really—fake Florida winter, the sweet earthy smell of sea grape trees and the rustle of lizards darting in and out of bushes.

A woman with blonde hair walks into frame and steps up onto the platform. She begins quietly removing her clothes, unzipping a Victoria’s Secret PINK tracksuit to reveal a string bikini spangled with the American flag. She slips off a pair of knee-high combat boots and places them upright like little soldiers next to her neatly folded clothes, leaving her barefoot and half-naked in her stars-and-stripes bikini. In the background, faint vehicular noises fuzz up into a monotonous song. She picks up a leather flogger, similarly printed with the American flag, and, beneath the clouded Florida sky, delivers strike one of 673.

The piece is one installment of four in artist Molly Jae Vaughan’s performance series, Atonement for Imaginary Sins. In these filmed performances, Vaughan delivers self-inflicted blows for extended periods of time, until her skin glows red. The text accompanying the piece explains: “673 strikes, one for each proposed anti-trans bill in the USA in 2024. No matter what you try to do, we will always stand firm and resist.”

The 24-minute video, initially posted to Vaughan’s Instagram on November 20, 2024, was recorded in Tampa at the University of South Florida (USF), Vaughan’s alma mater and former employer. Other versions were performed in Washington, D.C., in front of the U.S. Capitol Building; at James Harris Gallery in Dallas, Texas; and in Mobile, Alabama, at the Alabama Contemporary Art Center.

Despite their pared-down production, Vaughan’s performances through the Southern states were anything but simple to accomplish. She wanted to enact the piece in Tallahassee, but a contact at the ACLU in Florida told her in no uncertain terms that she would be arrested if she did. Even though the ACLU itself publishes a pamphlet on how to properly protest in Florida, as a trans person protesting, the rules aren't necessarily the same. So she decided to go to USF instead, where she had friends in the faculty. At 8 o’clock in the morning, while students slept off the previous night’s keggers, Vaughan went unnoticed on campus, tripod and flogger in tow, preparing to endure a stream of self-inflicted pain.

+++

Vaughan did not hear the word transgender until she was 23.

Nowadays, she calls herself a “transsexual,” and she doesn’t really care if it’s outdated.

“I use a lot of old-school terms toward myself,” Vaughan says. “Doesn't mean that they're the right terms for everyone. This is me talking about me. Let anybody be whatever they want to be, but don't fucking tell me I can't call myself a transsexual.”

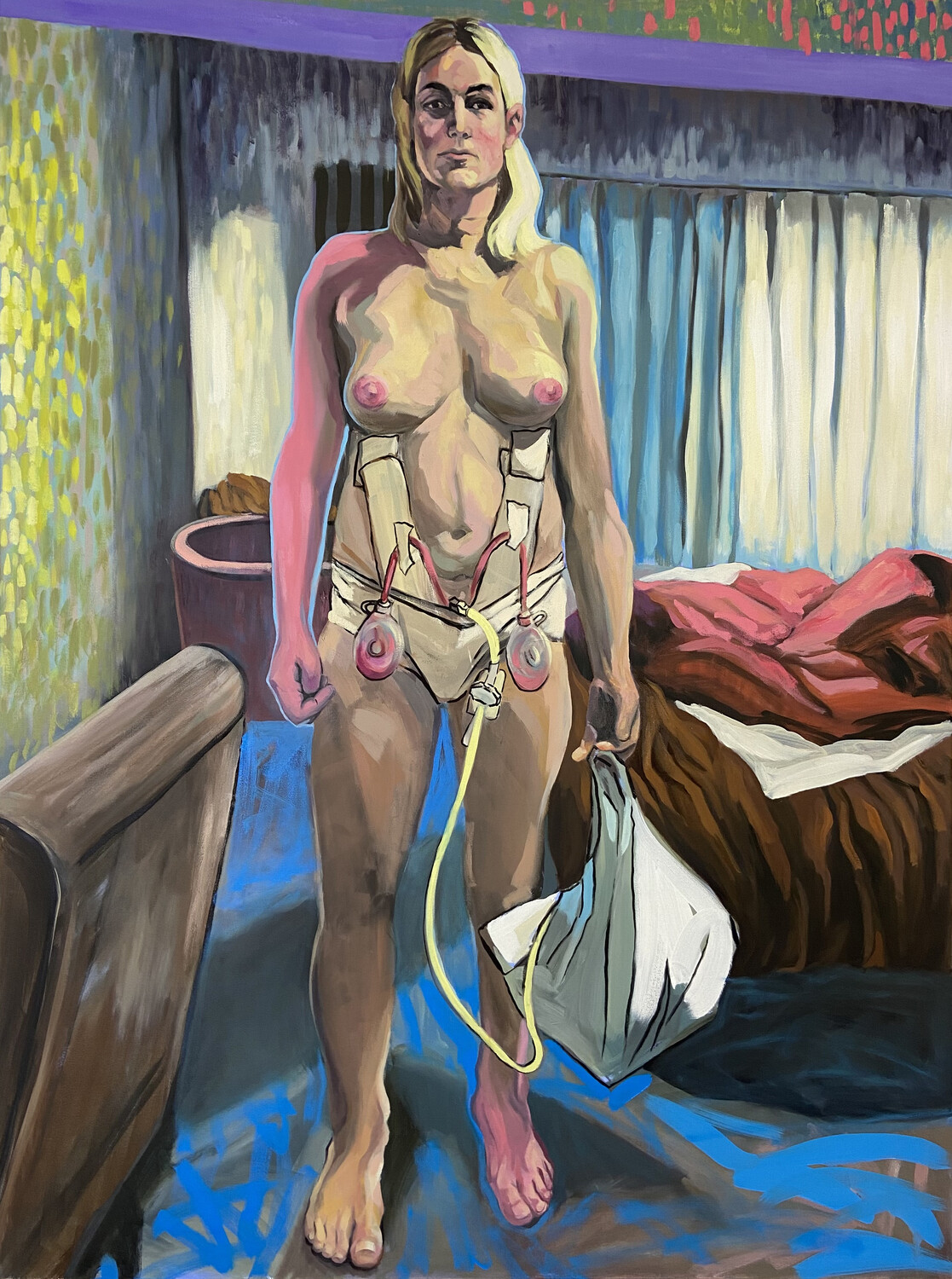

Vaughan is seated in a small studio in SoDo, in a building mostly unmarked from the outside—Google Maps won’t help you there. Inside, it’s full of every type of art, from textiles to almost-life-size self-portrait paintings to silk-screened prints. Stacks of posters that read “Republican Lies Kill Trans People” are on the ground next to swatches of fabric and buckets full of used brushes. It smells industrial, the acrid scent of oil paint layered with notes of damp coffee grounds. One painting hangs prominently in the center of her workspace: a 4-foot-tall oil on canvas depicting Vaughan after bottom surgery (or vaginoplasty), standing in front of her bed, pelvic area fully bandaged. Out of the gauze, two medical drains dangle down her front. A catheter tube leads down her leg and into the drainage bag she holds in one hand. On her face, a look of complete serenity.

The day of our first meeting is January 11. Vaughan is putting finishing touches on this painting and others before transporting them to Seattle University’s Hedreen Gallery, in preparation for her solo show Transition as Performance, Life as Resistance, which will open a few days later. Her exhibit includes the aforementioned painting, titled The Realization of Transsexual Dreams, as well as six other oil paintings. Along with these, Vaughan is showing three of her four Atonement videos, projected large against one wall, as well as screenprinted posters, Polaroids, and textile work, including flags designed as part of Project 42.

The latter is Vaughan’s best-known and most widely shown work. Project 42 is an ongoing memorialization of murdered transgender Americans in the form of handmade garments and flags printed with ornate geometrical patterns in bright colors—shocks of magenta, deep purple, blue. On a closer look, the kaleidoscopic prints appear to be made from fragments of a photographic image, mirrored and repeated. It’s a technique that Vaughan consistently employs in her work: a layering of challenging subject matter within beautiful designs or paintings, ensnaring the viewer with beauty before the reveal. For each garment in the Project 42 series, Vaughan begins with a Google Earth screenshot of the exact location of the murder of the trans woman to be memorialized. The image is then manipulated by photo editing software until it’s become a nearly unrecognizable abstraction. As with all of Vaughan’s work, the numbers are never arbitrary. Forty-two is the average life expectancy for a transgender person in America.

Despite her multidisciplinary and diverse body of work, Vaughan’s first love—“a spiritual connection,” she calls it—was painting. Her father hailed from a long tradition of British watercolor painting.

Born in London in 1977, Vaughan grew up in Heswall, a small coastal town in England, until she was eight and her family moved to Orlando. Her father, an international salesman for a pay phone company, traveled for work and always dreamed of bringing his family to the U.S. Her mother, employed as a hairdresser in the United Kingdom, found work in medical office management once they arrived in the States. Though her father was often far afield, Vaughan has fond memories of painting alongside him when he was at home.

This love of painting stayed with Vaughan into adulthood. She went on to pursue a BFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York, a brief stint in the Northeast after which she returned to Florida. Vaughan taught art at public schools and community colleges across the state before getting an MFA from the University of South Florida, where she stayed on as an adjunct professor of visual arts and painting, as well as at the University of Tampa and New College of Florida. It was in these classrooms that she finally began to socially transition as a trans woman.

“I didn’t come out. I just did it,” Vaughan says. As she began to explore and accept her trans identity, Vaughan felt a responsibility to be an example for her students: a trans person existing as they are, mid-transition, in higher education. The decision to not hide herself in her professional life was deliberate. However, with the rise of extremely conservative politicians such as Governor Ron DeSantis, Florida began to feel markedly less welcoming toward LGBTQ+ individuals with each passing year. For fear of losing arts funding, state schools behaved as though held hostage by government rulings, and places where Vaughan once felt safe to publicly transition no longer invited her to speak on campus.

In 2015, Vaughan relocated to Seattle to accept a position at Bellevue College, where she is currently a senior associate professor of art. But even in the Pacific Northwest, safety is not guaranteed, as Florida isn’t the only state that has been ramping up anti-trans rhetoric and legislation. In 2024 alone, the ACLU tracked over 500 anti-trans bills across the U.S., including both state- and federal-level legislation. While only a fraction of those bills were passed, they marked a dangerous uptick in transphobia coming from the American right. Many of these proposed laws target individuals’ right to gender-affirming health care, for both minors and adults. In 2024, the UCLA Williams Institute found that 113,900 transgender youths live in states that ban gender-affirming care. During the recent election cycle, misinformation about transgender youth receiving operations ran rampant. Despite the transgender community gaining visibility and representation in pop culture, to be trans in 2025 is to have your body—often your genitals—on the frontlines of political debate.

+++

Vaughan’s own body is a recurring centerpiece in her art. In Atonement for Imaginary Sins, she makes an offering of the skin on her back as a demonstration of the pain caused by transphobic politicians and policies. Vaughan notes that there is a sacrificial element to these performances. “There's a reason why I would never let another trans person do [Atonement],” she says. “As a transsexual woman, my body is political. As a white transsexual woman, as a member of the trans community, my body is the one that will suffer the least.”

As a white member of the trans community, Vaughan is up-front in talking about race and privilege as it affects her work. The overwhelming majority of murdered trans women are trans women of color. With Project 42, she knows that she cannot memorialize these women without thinking and talking about race. Yet Vaughan is wary of falling into a common trope among white queer people: the hollow romanticization of Black trans suffering. Remembrance is not enough without action, and Vaughan has made a point of keeping her work inclusive of the communities she seeks to represent in her art. When exhibiting her work at the Seattle Art Museum in 2018 on the occasion of winning the Betty Bowen Award, Vaughan showed a dress created in honor of the life and death of Deja Jones. At an unpublished memorialization event planned in tandem with the exhibition, she invited Randy Ford, a Black trans performer, to remove the dress from the wall, put it on, and dance—a deeply embodied celebration of the life of a trans woman of color.

“If I have a five-hundred-dollar budget for a performer,” Vaughan explains, “I want to get that money to a Black trans woman. Let's get them in here, let's make sure they're getting museum credit. Let's make sure they're being recognized in the work, and not just for their suffering.”

It’s in Vaughan’s paintings, like The Realization of Transsexual Dreams, that she explores her profoundly personal experience of living in a transsexual body. Steeped in historical precedent—think classical depictions of the effortless feminine beauty as depicted in the female nude, from Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque to Titian’s Venus of Urbino—Vaughan’s self-portraits play with our expectations of a traditional style. In Lying in the Bed of my Divorce, one of a series of six oil paintings on canvas displayed at Hedreen, Vaughan depicts herself lounging in bed, a body at rest, luxuriating and half-dressed, amid a heap of crumpled striped sheets. In Silicone Joy, she holds her own breast to her open mouth, taking pleasure in her body. It’s playful, sensual, sexy—a moment of humor.

Displayed next to her paintings is a collection of Polaroid prints titled The Brutality of Change: Photographic documentation of transsexual technology. Again, her body is the subject, though to a much different effect. The photographs follow her surgical transition through multiple operations: vaginoplasty, breast augmentation, facial feminization surgery. They are deeply intimate windows into a process of change, which she refers to as “medicalization,” and indeed, they show her body as a product of great medical achievement. With each successive work of art in the exhibit, the viewer is drawn more closely into Vaughan’s personal experience, until we are brought face to face with the uncensored truth of her body.

“We're going to display my needles at Hedreen,” she says. “I have no problem telling you that I'm a trans woman. I have no problem telling you that I had bottom surgery. I have no problem telling you that I have silicone breasts. I don't care because I fucking fought for this. I'm proud of this. Like, they just took part of my face off and rearranged it. That's fucking badass, right?”

Underneath the collection of Polaroids at Hedreen, Vaughan’s needles are indeed displayed, the same kind used daily by many trans women to administer estrogen. They are collected in empty Florida’s Natural juice containers; the piece is aptly titled Girl Juice.

+++

On January 20, five days after the opening of Transition as Performance, Life as Resistance, a small crowd trickled in and out of Hedreen Gallery, visitors toting worn T-shirts and hoodies. Vaughan invited the community to gather for a BYO T-shirt screen printing event, where a group of assistants stood ready to print clothing and posters with Vaughan’s rallying cries, like “HOLD FIRM FOR THE POWER AND GLORY OF TRANSNESS IS ETERNAL.”

Marked by both Martin Luther King Day and the presidential inauguration of Donald Trump, the day is charged; trans rights are hanging in the balance more than ever. Because of this—or in defiance of it—Vaughan has turned the gallery into the site of a happening, a place for political resistance art and gentle acts of protest, if only for a few hours. Along with silk-screening, visitors are encouraged to take from stacks of sparkly stickers printed with words of trans empowerment. The moment reverberates with the historical, specifically harkening to ACT UP, a movement to raise awareness of the AIDS pandemic in the ’80s and ’90s. As with the materials being created in Vaughan’s makeshift factory at Hedreen, ACT UP’s goal was to inundate the landscape with slogans and signage so eye-catching, they couldn’t be ignored. Their SILENCE = DEATH posters and stickers could be found on almost every block of New York City at the time.

It is in this spirit that the night unfolds, in a room filled with moments of transsexual and transgender joy. Vaughan has a friend’s baby on her hip and glittery pink eyeshadow in the corners of her eyes. Visitors will inevitably go home to news of more anti-trans legislation being written and signed, but for now, being in this space among Vaughan’s art is a powerful antidote and a way forward: life as resistance.

Molly Vaughan can be found on Instagram at @vaughanprojects. Her show, Transition as Performance, Life as Resistance, is on view at Hedreen Gallery through March 29.