From Weapon to Wonder

How Ralph Ziman uses 70 million beads to tell a story of transformation

From Weapon to Wonder

How Ralph Ziman uses 70 million beads to tell a story of transformation

In a warehouse in East Los Angeles, a 51-foot long fighter jet with a wingspan of 24 feet awaits its final embellishments before being loaded into a truck and driven up the coast to Seattle, where it will be exhibited for the first time to the public—as a work of art. Countless panels of brightly colored chevrons, stripes, and herringbone patterns zigzag across every inch of the machine—a full rainbow spectrum of sunny reds, oranges, and yellows that graduate to deep turquoise and purple. On closer examination, you’ll find the patterns are made up of tiny glass beads—70 million of them.

The jet is a Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21, the real aircraft after which the fictional MiG-28 in Top Gun was based. Designed by the Soviets and renowned for its supersonic speed and agility, the MiG-21 is the most produced supersonic fighter jet in history, with more than 10,000 manufactured since the early 1960s. Several national air forces still use the MiG to this day, including those of India and North Korea.

This particular, very bedazzled MiG had been out of commission for decades, sitting idle on a runway in Lakeland, Florida, until Ralph Ziman decided to give it a new life as part of his ongoing 12-year-long project, Weapons of Mass Production. According to Ziman, sorting out the logistics of sourcing and transporting a fighter jet from Florida to LA was the easy part.

“Once we had it in the studio, you look and go, ‘Oh my god, what have we done?’” Ziman said on a recent call from his Los Angeles warehouse-turned-hangar. “This thing is huge! The surface areas are huge. The wings, the tail fins, the tail, everything…”

How he arrived at this point in his career was not exactly a straight path. Ziman was born in 1963 in Johannesburg, South Africa, deep in the midst of apartheid. At 19, when conscripted to join the South African Army, he fled the country as a conscientious objector.

“I just felt at the time that I could never justify serving in the South African military,” Ziman says. “I was raised with Black people. I was very close with them, so the thought of putting on that uniform, for me, would have been intolerable.”

Ziman ended up in London, where he found work making music videos—one of few industries in England at the time that had lax regulations for a young kid lacking citizenship. Over the next three decades, he directed and worked on music videos for some big names: Ozzy Osbourne, Vanessa Williams, Rod Stewart, Michael Jackson, and Rick James, to name a few. He also wrote, directed, and produced a number of independent feature films which dealt with themes of apartheid, including 1995’s Hearts and Minds, the first independent South African feature film to be released after apartheid. Despite his success in the industry, film was never his primary passion; as a child in South Africa, Ziman loved to draw and paint. It wasn’t until 2013 that Ziman returned to fine art with his trilogy project, Weapons of Mass Production.

Approaching the subject with a cinematic eye for storytelling, Ziman sought to call attention to issues that continue to haunt South Africa but also weave throughout the international stage: the arms trade and emblems of institutional oppression like military vehicles and fighter planes.

The first part of the trilogy, The AK-47 Project, involved the creation of hundreds of exact replicas of AK-47 machine guns, which Ziman—with the help of an assembly of Zimbabwean makers—then decorated with colorful beadwork in patterns traditional to Zimbabwe and South Africa. The next chapter, spanning from 2015 to 2019, produced The Casspir Project, in which Ziman and his team undertook the transformation of a decommissioned Casspir—the massive, imposing police vehicle Ziman knew as an everyday fixture of his childhood in the ’70s and ’80s in South Africa. He recalls seeing policemen sitting atop the vehicles, brandishing heavy machine guns—a ubiquitous image of apartheid rule. Ziman notes that the Casspir eventually found its way back into a wider cultural vernacular when it started appearing to patrol Black Lives Matter protests in the US.

“You have this South African police car designed by a white fascist government to oppress Black people, and here, it winds up on the streets of America 40 years later, with white cops sitting outside, policing Black Lives Matter,” Ziman notes.

Calling attention to such echoes of apartheid is part of the message Ziman hopes to convey through the transformation of weapons. He also wants to showcase the craft once shunned by many white South Africans but tied to a community he considers family, and to Ndebele woman who helped raise him as a young child. The Ndebele are an Indigenous community of South Africa’s Mpumalanga Province, known for the intricate geometric patterns and vibrant colors of their beadwork.

“During the apartheid era, it was looked down upon amongst South Africans,” Ziman says of the traditional beadwork now covering his MiG-21. “It was considered a low craft—curios made for tourists by Black people. If you said you wanted it, people would say, ‘Why? It's rubbish.’”

It was important to Ziman to highlight both the craft and the immense skill exhibited by such artisans like his former Ndebele caregiver, who demonstrated the craft to him as a child. For The Casspir Project, Ziman worked out of a studio in South Africa with a team of beadworkers and artisans—most of them men and women from rural townships—to complete the mammoth task of covering every inch of the vehicle with glass beads. Over the years, Ziman has developed close relationships with the artists who have worked on his teams to realize the projects. One of his closest collaborators, Thenjiwe Pretty Chinedo, is an Ndebele woman and the founder of Anointed Hands, a collective dedicated to keeping the art of beadwork alive.

The pair met a decade ago at Chinedo’s store in Rosebank, Johannesburg, where she continues to sell jewelry and beadwork made by herself and the women in her collective. She came on board for The Casspir Project, traveling across the country each week to deliver Ziman’s color-coded designs printed on cardboard to groups of women. Every week, Chinedo collects the finished beadwork and drops off new designs. Through Ziman’s projects, she has been able to provide a steady source of work and income for hundreds of women across rural areas of Mpumalanga.

Ziman was in the middle of making arrangements for his South Africa-based team to come to LA to work onsite for the MiG-21 project when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Hopes of getting visas cleared for everyone were already slim during the Trump administration, but with COVID, it was impossible. The only option was to ship the color-coded designs to South Africa and back, an unwieldy process that took five years to complete.

Now, the MiG is covered in beads everywhere, even the cockpit, which looks like a Lisa Frank coloring book meets psychedelic Candy Land. The seat is quilted leather with pops of cheetah print, and the flight stick has been replaced by a chrome chain steering wheel. The only parts not covered in beads are painted glossy candy apple red and pinstripe—an explosion of references to East LA’s lowrider culture mixed in with the traditional South African elements.

“Often, we'd have these lowrider cars bumping outside the studio,” says Ziman. “So we thought, wouldn't it be great if we just gave a nod to East Los Angeles and hot rod culture?”

Along with these little love notes to LA, the MiG is also ripe with symbolism that speaks to the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Ziman’s decommissioned MiG was fabricated by the Soviet Union. Part of transforming the weapon into a piece of art is, for him, a nod to Ukraine and acknowledgment of the colonial kleptocracy taking place as Russia wages war—more echoes of apartheid. The flamboyant colors of the MiG and its cockpit take the message even further.

“At some point, Putin declared that there aren't gay people in Russia,” says Ziman. “Well, we thought we'd take this cockpit and make it the glitteriest, sparkliest, gayest cockpit there is.”

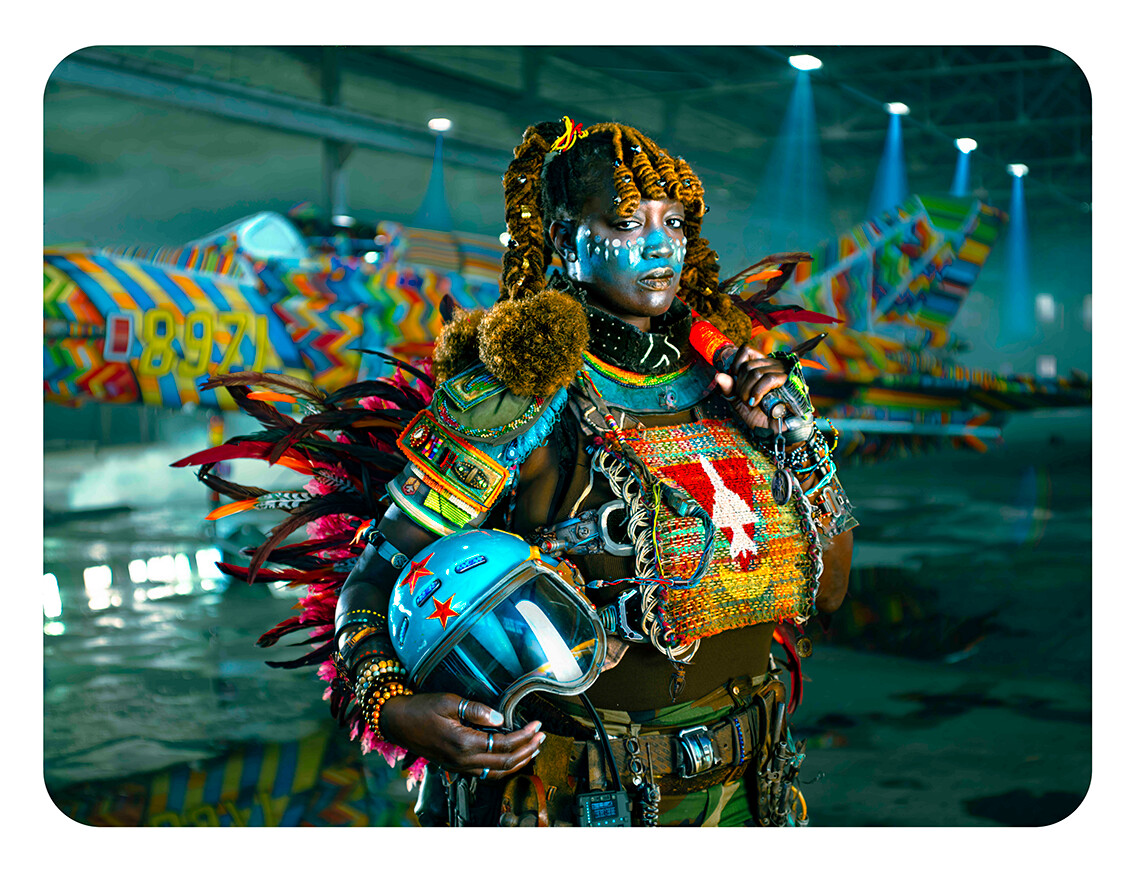

Last summer, Ziman brought The Casspir Project to Seattle, where it was exhibited at Seattle Art Fair, as well as galleries Railspur and TASWIRA. This year, on June 21, the MiG-21 will be unveiled for the first time at Seattle’s Museum of Flight. The jet will be accompanied by an exhibit of photographs as well as Regalia, a collection of altered and embellished military garb verging on science fiction—fantastical space suits straight out of Dune, except they’ve been augmented with traditional African patterns. It’s a twist on an Afrofuturist reimagining of past and future for South Africans and beyond.

But such reimagnings are more than mere fantasy. By disarming the darkness, Ziman proves we can transform even the largest, heaviest ghosts of our cultural past into something beautiful, and strewn with hope. ◼︎

The MiG-21 Project is on view at the Museum of Flight from June 21 through January 2026. More info at museumofflight.org.

Maxine Arnheiter is a writer and the assistant editor of Public Display Art.