20 Years of Onyx Fine Arts Collective

A legacy built on grit, glitter, and the grind

20 Years of Onyx Fine Arts Collective

A legacy built on grit, glitter, and the grind

Tucked into the fourth floor of Seattle’s half-empty Pacific Place mall, past shuttered storefronts and a stark empty atrium, a gallery pulses with life. Gallery Onyx, run by the The Onyx Fine Arts Collective, is part sanctuary, part revolution, and has spent two decades turning overlooked corners into cultural landmarks. Founded in 2005 by retirees and artists fed up with exclusion, the collective isn’t just filling gaps in the Pacific Northwest’s art scene; it’s rewriting the rules.

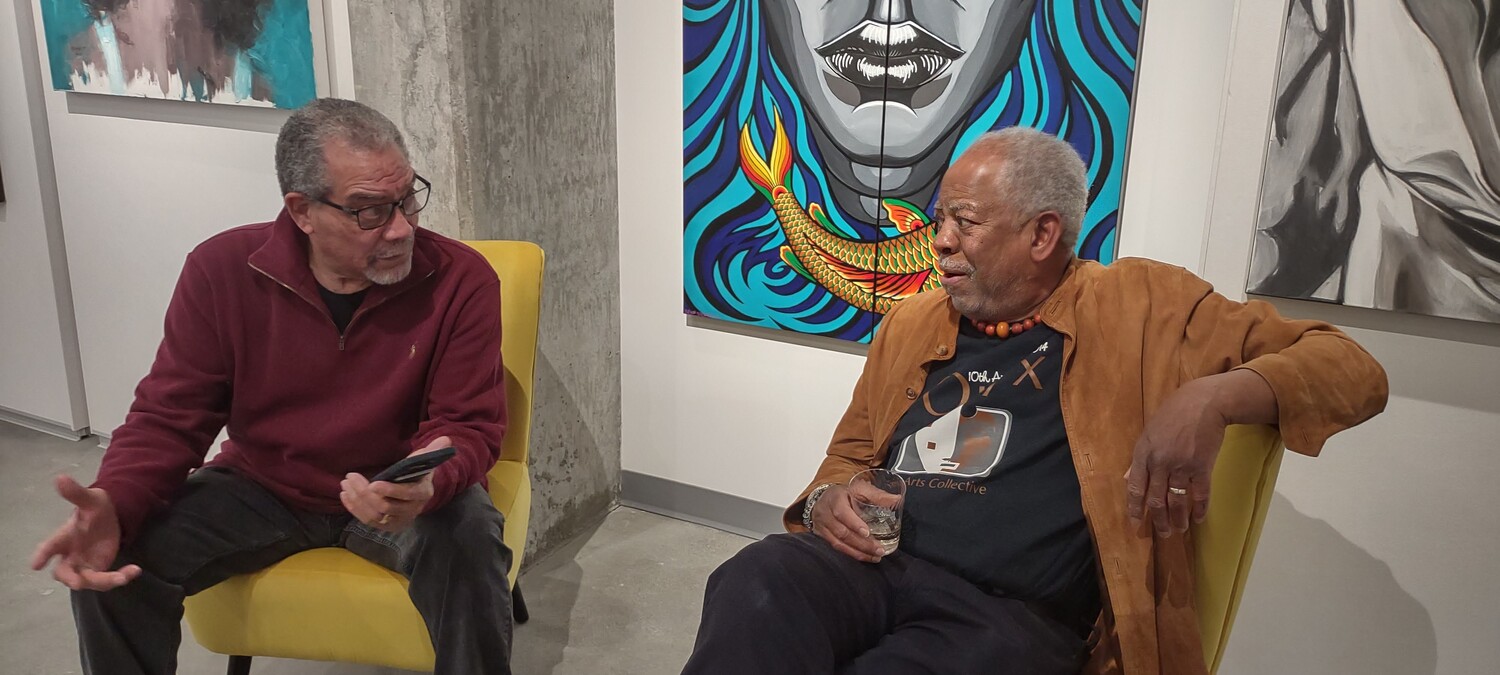

“Galleries acted like Black artists were invisible,” says cofounder Earnest “Earnie” D. Thomas, his tone equal parts defiance and pride. “So we created space. No apologies.”

Growing from six founders to over 800 artists, Onyx has evolved from small gatherings in living rooms to a gravitational force across the region for Black creatives. Their secret? Meet artists where they are—even if “where they are” is a library in eastern Washington or the lobby of the Edith Green–Wendell Wyatt Federal Building in downtown Portland.

As a result, their reach stretches far beyond Seattle—places such as the Tri-Cities, a region of Washington better known for nuclear reactors than nude sketches. When the collective hosted a show at the Richland Public Library in 2016, the response was electric.

“Black folks in Hanford were hungry for art that reflected them,” says Ashby Reed, a painter and founding member. “The line wrapped around the block.” Portland followed, with pop-up exhibits that caught the eye of local dignitaries and quietly challenged the city’s homogeneity. “Portland’s art scene needed a jolt,” Thomas says. “We brought our truth.”

Today, the collective’s influence ripples globally. Artists from Lagos to London inquire about collaborations. Collectors in New York and Atlanta snatch up pieces by artists who’d never shown in a gallery before Onyx. A 7-year-old’s abstract painting? Sold to a buyer in Chicago. A retired Boeing engineer’s sculptures? Displayed in City Hall. “Our artists are everywhere now,” Reed says. “But our roots? Still here, in the Pacific Northwest.”

One of Onyx’s signature events, their annual juried exhibit featuring Pacific Northwest artists of African descent, is more statement than show. The event and exhibit is unapologetically inclusive; it’s where quilts stitched with protest lyrics hang beside bold, digital collage and oil paintings of Pacific fog. “We had a father and son exhibit together last year,” Thomas recalls. “The kid sold his first piece and sobbed. His dad’s work hung right beside his. That’s how legacies grow.”

Absence of hierarchy is central to the collective’s ethos. A 90-year-old sculptor mentors a teen graffiti artist. A software engineer-turned-watercolorist shares walls with a Guggenheim Fellow. “We’re not about ‘discovering’ talent,” Reed insists. “Talent’s already here. We just turn on the lights.”

Let’s be real: Onyx’s journey wasn’t all gallery openings and applause. Early shows were funded out of pocket, starting in living rooms and then moving to city buildings, host galleries, and eventually museums, steadily building momentum along the way. In 2015, they held an exhibition at a gallery on First Avenue in Belltown—a welcoming space owned by a low-income housing group. While they weren’t looking for a permanent home, the success of the show led to an offer they couldn’t pass up: a chance to use the space regularly. This marked a turning point, giving Onyx a consistent presence for the first time. They continued hosting ever-larger juried shows across the city, including a massive 2017 exhibition on the third floor of King Street Station, which drew a huge crowd. Their partnership with the housing group made an even bigger impact, as the group acquired Onyx artists’ works for housing developments.

When the collective was eventually forced to leave the Belltown space in 2018, on account of renovations, it pivoted to an opportunity offered by developers looking to fill unused spaces in the mall. “Pacific Place wasn’t our first choice,” Thomas admits, “but once we were shown the space, we saw the vision and knew it was going to be amazing.” Since having to relocate from the original space in Pacific Place (which is still under renovations), they are making the most of their fourth-floor gallery, where Gallery Onyx remains today.

Funding continues to be a puzzle. Onyx is a nonprofit arts collective with a board of directors and funds to raise. Grants help, but the collective leans hard on volunteers, sweat equity, and a loyal community. “We’re always hustling,” Reed says.

The hustle pays off, and as Onyx celebrates its 20th anniversary, the founders are focused on futures beyond their own. One recent undertaking: a self-published book featuring work by some 74 artists, with the aim of placing a copy in every public school in Washington. Meanwhile, a new generation of leaders is stepping up, blending fresh ideas with Onyx’s established DIY ethos. “We’re not just preserving culture,” Reed says, “we’re passing the brush.”

Thomas puts it more simply: “Walk into our gallery. See that 6-year-old grinning next to her first sale. Watch a Seattle transplant find their tribe. That’s why we’re still here. It’s one of the rare spaces in Seattle where emerging and established Black artists find their community and build their professional legacies.”